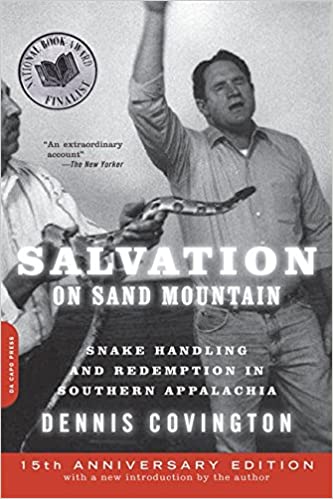

Salvation on Sand Mountain

First printed in 1995 and re-released with an updated introduction in 2009, Salvation on Sand Mountain is an autobiographical sketch by Dennis Covington about his experience first reporting on and then becoming involved in the culture of holiness snake handling in Appalachia. From the cover blurb:

The practices of Holiness traditions, such as handling snakes, drinking poisons, and so on, have always been of interest to me. I have never lived or participated in communities that incorporate these practices as part of their regular worship, so my awareness of the tradition was almost entirely through their sensationalized, fictional depictions in television, film, and literature. Always interested in Christian liturgy, ritual, and worship, learning more about this tradition (or traditions, more accurately) had long been on my endless list of topics to find and read about.

In 2020, the news about the upcoming film Hillbilly Elegy prompted much discussion in my social media circles about depictions of Appalachian culture in media. Most of my online acquaintances who had some connection to Appalachia felt that this film and many other popular depictions of Appalachia were unfairly exploiting long-held stereotypes about the region. Stereotypes which unhelpfully emphasized certain truths or half-truths about the region while ignoring the context that helped to make sense of them. In one of these conversations, snake-handling came up as an example of a misunderstood, overplayed stereotype. Someone asked for recommendations on what they could read that would present Appalachian culture, particularly snake-handling, more fairly. Salvation on Sand Mountain: Snake Handling and Redemption in Southern Appalachia by Dennis Covington was suggested by a number of people and so I sought it out.

I was concerned, early in the reading, the Covington might be falling prey to the same temptation as Hillbilly Elegy and its kin. To play up stereotypes about Appalachian people which made them seem strange and exotic to people from other places in the name of selling newspapers or books. Quotes like this one certainly serve to draw the reader in with a morbid curiosity and fascination:

However, as the book progresses, I think the shift in Covington's own stance toward the people and traditions in these snake-handling congregations is reflected in the writing style. He begins as a reporter, sent from outside to cover a particularly sensational court case whence this quote comes, and becomes an intentional, curious observer, and finally a participant in the communities he was sent to report on. As his relationships to these congregations change, so does his style of writing.

About a third of the way through the book, as Covington is realizing his own connections to the people of Appalachia through his family history, he offers some context for where some of the unhelpful stereotypes about the region come from. He describes Scotch and Irish immigrants who settle in the mountains of Appalachia and become a society of close-knit families with a self-sufficient culture. They develop their own variations of Anglicanism/Methodism and Presbyterianism which still include the ideas of good works and election, but also "free grace" and they often worshipped outdoors. In the nineteenth century, many of these people would be lured from their family homes of generations to work in coal mines and mill towns with the promise of higher wages and the encounter with a changed world outside of the mountains and valleys would shake their communities.

The particular religious culture and theology of these Holiness congregations comes out in Covington's reflections on conversations and experiences that he has among them. He recognizes that his own background in the Methodist tradition gives him and the snake-handlers some historical common roots, but he is consistently surprised at the claims to authority that the preachers and miracle-workers among these congregations make. Early on in his travels, Covington meets a preacher and snake-handler named Charles McGlocklin who explains some of the history and tradition to him. Key to the tradition, along with the ideas of election and free grace, is the idea that after "new birth," there occurs a second act of grace often called the "Baptism of the Holy Spirit," which was the beginning of a process of purificiation; growth in holiness. Signs of one's growth in holiness were expected to manifest in spiritual gifts mentioned in scripture: signs and wonders, healing, prophecy, casting out unclean spirits, and speaking in tongues. Among the signs and wonders were the capacity to handle venomous serpents and drink poisons without ill effect. These signs were critical evidence to the congregations of the presence of the Holy Spirit in their lives and the faithful of God to promises made. These were not to be fulfilled at some distant future date, but were being acted upon in the here and now. In one conversation about the differences between a mainline tradition like Covington's Methodism, McGlocklin says to him,

At first encounter with the idea of a Christian tradition centred on preaching, singing, and displays like the handling of snakes, it's easy for someone from a mainline Western tradition—someone like me—to shake their head and write it off as strange and a bit silly, unnecessary, and dangerous. In fact, I think this response is precisely why there are so many uncharitable stereotypes and jokes about the people who participate in this tradition. Whether it's the sensationalism of the news story Covington was first sent to cover, a preacher who tries to kill his wife with venomous snake bites, or a throw-away joke between Homer Simpson and Moe Syzlack, the latter's hands covered in bites and bandages while he says "I was born a snake-handler, I'll die a snake-handler," ("Homer the Heretic") the idea that certain religious practices are questionable and belong on the fringes is not a new one.

The charge of "enthusiasm" was levelled against many of the Christian sects which formed in the seventeenth century whose practices did not conform to those of the cultural majority. Quakers and Methodists, for example, were often accused of "enthusiasm"—another term for madness or possession by a spirit at the time—because of the departure of their worship practices from the norms of the Church of England at the time. (Charles Cherry, "Enthusiasm and Madness: Anti-Quakerism in the Seventeenth Century"; Eric Baldwin, "The Devil Begins to Roar: Opposition to Early Methodists in New England") Along with the charge of enthusiasm almost always also come claims of immorality and an unfitness to be considered "proper" Christians: thievery, sexual assault, uneducated preachers and leaders, and so on. In the case of snake-handling congregations, the Methodist tradition is one of the influencing traditions on the Holiness movement and the dismissiveness of mainline Christians and non-Christian observers toward these congregations may also be something of an inherited legacy alongside a contemporary judgement.

What I find most interesting about this history and the current treatment of these Holiness congregations is that while the manner and form are certainly different to what I preside at in an Anglican Church of Canada liturgy, I am not so sure that the core principles being acted upon are so different. There are some sociological factors to be aware of while considering the differences and behaviours of the Holiness congregations compared to mainline churches. Sociologists of religion have offered that there is a value to religious communities in having a degree of cost to their "buy-in" for members. There need to be factors which separate this community from others and there needs to be an investment required of members for it to register as a valuable commitment. Put another way, communities which demand nothing of their membership have trouble persuading members to remain as there is no perception of value in what is offered. Effectively, it's worth what you're paying for it. This can go too far the other way, of course. If too much is demanded and too little offered in return, members will leave having perceived that they are being exploited. (Judith Shulevitz, "The Power of the Mustard Seed: Why Strict Churches are Strong"; Laurence R. Iannaccone, "Why Strict Churches are Strong")

There is also the phenomenon of "credibility enhancing displays" to consider. These are usually extravagant, costly displays meant to demonstrate and reinforce belief in religious claims, usually to the presence and power of a supernatural agent. These displays might be acts such as ritual scarification, firewalking, animal sacrifice, or perhaps snake-handling and the drinking of strychnine. These displays have been shown to reinforce deep levels of belief and commitment to the group, supporting cooperation, shared belief, and ideology. (Joseph Henrich, "The evolution of costly displays, cooperation and religion: credibility enhancing displays and their implication for cultural evolution"; J. A. Lanman & M. D. Buhrmester, "Religious actions speak louder than words: exposure to credibility enhancing displays predicts theism")

However, sociology and cognitive science of religion aside for a moment, what intrigues me is that the central claim of both an Anglican eucharist and a snake-handling event is the same: that God has promised to show up and do something and that those in attendance can trust that God will keep the promise. The Holiness congregations believe that those who are filled with the Spirit can handle serpents, drink strychnine, prophesy, and perform healing miracles because God is present and will make it possible. Is this so different than the prayers of "Hosanna!" in a eucharistic liturgy? (Hosanna, roughly translated, means "Come and save us".) Anglicans pray that God will be present, that the Holy Spirit will be sent upon the congregation and the eucharistic gifts before them.

The Anglican Communion does not hold to memorialism, receptionism, or transubstantiation as explanations of the eucharist, but it does hold that something extraordinary happens to the bread and wine in the eucharist:

This statement was expanded upon later, due to concerns about the use of "become" in describing what happens to the bread and wine:

Were it not for the centuries-long cultural normativity in the West of Christian eucharistic practice, would the above claim about the changing of bread and wine into body and blood not seem at least as strange and outlandish as the proposal that one might dance with a rattlesnake and not be bitten? Or that one might drink strychnine without serious consequence? It seems reasonable to me that the People of God can and should expect to see and experience sacraments and sacramentals in their lives. If the power of the Holy Spirit includes the entrusting to humanity gifts described in scripture, then we should expect to see those gifts in evidence in our communities.

I am not trying to make claims about the validity or sacramentality of snake-handling Holiness congregations here. Reading one memoir of a man engaged with those congregations for a time is not nearly enough material to undertake that work with any credibility. But it does seem to me that, at the very least, Holiness congregations are following a properly Christian impulse: to find and encounter God where God has promised to be found. How we determine the places and times and even details of God's promises are the story and history of countless conflicts and disagreements among Christians, well beyond the scope of this article. The danger of handling venomous snakes and of drinking poisons cannot be overstated and are not events in which I can imagine myself participating, nor many other Anglicans known to me. But the work these congregations are undertaking, however unusual and dangerous they may seem, appear to be born of a desire to know and see God more intimately and more thoroughly and an acknowledgement that God wishes to see and know us.

In sum, this is a well-written, interesting, and accessible book. It offers a glimpse through Covington's eyes into a culture entirely foreign to me, but which prompted fruitful and interesting reflection on my own religious practices and how I react, rather than respond, to the practices of others. This would make for excellent casual reading for anyone interested and could be used as a book study to prompt discussion about how we engage with and perceive other cultural groups and religious practices. Highly recommended.